Industrial Strategies [Expanded]

- C. Tomlinson

- Nov 29, 2021

- 36 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2024

An abridged and edited version of this essay was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Arts Entrepreneurship Education, and the study's findings were presented alongside an extended discussion at USASBE 2022. This version includes preliminary notes for a cut section on Cabaret Voltaire, as well as an extended conclusion discussing industrial music's metaphors and legacy.

Industrial Strategies

Rhetorical theory at the intersection of Arts and Entrepreneurship

Abstract

By emphasizing the rhetorical processes integral to arts entrepreneurship, this study hopes to open up a rhetorical vocabulary that will simultaneously expand Arts Entrepreneurship discourse and bridge the gap between its constituent terms. Likewise, the abstract processes of rhetoric offer an insightful perspective on the specific processes of entrepreneurship in the arts. The first wave of Industrial Music in the late 1970s and early ‘80s is taken as a case study in order to articulate how a group of artist-entrepreneurs used information, attention and sound itself as rhetorical tactics to engage in an emancipatory form of Arts Entrepreneurship. In step with these objectives, my rhetorical model tethers notions of socio-aesthetic attack and emancipation to a critical rhetoric informed by poststructuralist thought. The resulting analysis shows how Industrial artists used rhetorical tactics as entrepreneurial bricolage to both span and challenge the divide between business, artistic and social practice.

Introduction

The challenge of defining and theorizing arts entrepreneurship has been well discussed, as has the importance of both for developing arts entrepreneurship curriculum (Beckman, 2014; White, 2015). This difficulty can be attributed in part to the elusiveness of its two constitutive terms, as well as the perceived tension between artistic and business interests and concerns over reducing art to a monetary value (Beckman, 2015; Zabel 2016). Compounding this latter difficulty is how the image of the entrepreneur remains bound up in hegemonic discourses that reinforce neoliberal conceptions of the rational and self-determined individual, and potentially reproduce systemic inequality (Aldrich, 2005; Dannreuther & Perren, 2015). Conversely, scholars have suggested that entrepreneurship offers autonomy and emancipation (Rindova, Barry, & Ketchen, 2009), and that artists in particular take on entrepreneurial roles for the sake of artistic and economic freedom (Essig, 2015).

Other writers have challenged the idea of a mutually exclusive relationship between financial and artistic interests, suggesting a similarity or fundamental sameness between processes of art creation and entrepreneurship, as well as between their respective skillsets (Hart & Beckman, 2015; Scherdin & Zander, 2011). More specifically, these authors collectively describe how both processes necessitate effectual (Sarasvathy, 2001) and divergent (Guilford, 1959) thinking in response to new and unique problems, and how these responses have the potential to effect changes throughout broader economic, social, and/or aesthetic systems. This latter notion resonates with the diverse and influential thinkers who have defined entrepreneurial innovation (Schumpteter, 1942/2003; Becker, 1983/2008) and artistic creativity (Deleuze 1987/2007; Csikszentmihalyi, 1996) by the disruptive effects they have on their respective domains, interrupting existing discourses and opening new possibilities. [1]

In order to move forward in circumscribing and theorizing the field, I suggest that tending particularly to Arts Entrepreneurship’s suasive dimensions would help carve a path for the productive import of a wide array of rhetorical theory – both time-tested and cutting-edge – into the scholarship. Rhetoric, the ancient art and practice of persuasion, has already been adopted as a set of valuable (if underutilized and occasionally reductive) tools for business scholars and practitioners (Hartelius & Browning, 2008), including those in entrepreneurship (Spinuzzi, 2017). In this interdisciplinary appropriation of rhetorical theory, however, arts entrepreneurship in particular remains unaffected. By treating arts and entrepreneurship (both separately and together) as rhetorical phenomena, I forward a perspective on Arts Entrepreneurship which does not bracket off the artistic and economic activities of the arts entrepreneur, but which rather treats each as different manifestations of a unified process of persuasion, contingency, and invention.

This study intends to demonstrate the usefulness of a response-oriented rhetorical mindset for synthesizing artistic and entrepreneurial practices, as well as to suggest a small sample of rhetorical techniques which themselves bridge the gap between the two by way of their focus on mobilizing effects. What follows is therefore a set of practical tools for responding to contingencies and finding new emancipatory spaces, as well a mode of analysis for arts entrepreneurship educators, researchers, and theorists.

Rhetoric and Entrepreneurship

Definitions of rhetoric, particularly in the last century, tend to cast it as a broad phenomenon that can easily be understood to encompass all symbol usage. The scope is typically narrowed by tethering rhetoric to persuasion, a defining element articulated since the discipline's genesis by Plato and Aristotle. [2] Following a number of seminal works expounding material rhetoric since the 1990s (e.g. Blair, Jeppeson, & Pucci, 1991; Blair, 1999; Dickson, 1999), the domain of rhetoric expanded beyond symbol use and into the material world, setting the stage for what Barnett & Boyle (2016) describe as a rhetorical ontology. Under this paradigm, essential rhetorical phenomena of persuasion, contingency, and agency are not abstractions of purely social phenomena, but are instead a dimension (capacity) present at every level of being, always in effect to change the course of events from one possibility to another. In a continuing effort to re-circumscribe the domain of rhetoric, Muckelbauer offers two important points. First, rhetoric as a concept deals with response (i.e. effect) rather than content (signification) (2008). Second, rhetoric cannot be an object. It is merely a linguistic shorthand to say that x is an example of rhetoric, that rhetoric does x, or that x is rhetorical. Rather it is best thought of as a character, function, or – via Burke and Aristotle – capacity. Rather than a noun, "we might consider 'rhetoric' primarily as an adjective, or better yet, an adverb—that which modifies or qualifies actions in some way" (Muckelbauer, 2016, p. 40). To call rhetoric a type of communication (or vice versa) would therefore be a misrepresentation. More accurately, rhetoric is a capacity of communication, as it is a capacity of material objects, market forces, works of art, and other domains.

The practical application of rhetoric for constructing organizations and influencing markets has been welcomed into business fields like management, marketing, and entrepreneurship. [3] Given this productive history of cross-pollination, it is imperative for entrepreneurship educators to review the full range of rhetorical methods at their and their students’ disposal – not only how to use more diverse modes of rhetoric to influence, but how to critically examine one’s discursive environment in order to identify or construct resources and opportunities.

In business literature, the discipline of rhetoric has gradually overcome the inaugural Platonic prejudice against rhetoric as a dubious practice of manipulation. This mere rhetoric perspective, along with its more value-neutral descendant, managerial rhetoric, has gradually given way in business and other fields to a recognition of rhetoric as the persuasive force immanent in social interaction, with equal potential to misrepresent and positively construct (at least) social reality. It is using this broader conceptualization that Spinuzzi (2017) outlines the rhetorical activities of the entrepreneur as identity construction, community mobilization, and managerial persuasion. Nevertheless, not only has this understanding of rhetoric yet to be applied in force to entrepreneurship in the arts sectors, it has yet to incorporate some of the bolder implications of a rhetorical ontology, as I detail below. These two omissions are made all the more exigent by theory-building work in arts entrepreneurship (e.g. Essig, 2015; White, 2019; Callander, 2019) which increasingly recognize the process as uniquely persuasive, contingent, and concerned with agency, suggesting that a rhetorical understanding is necessary to further circumscribe the field.

Arts Entrepreneurship as Rhetoric

By faithfully and rigorously applying rhetorical concepts, arts entrepreneurship practitioners, theoreticians, and scholars immediately gain two useful tools. The first relates to epistemology and methodology. As a method of knowledge-making, rhetoric (an art of control, contingent on the available means of persuasion and inextricably linked with doxa, i.e. public opinion or “common sense”) has been traditionally contrasted with its ancient antagonist, the Socratic dialectic (a practice of prediction based on infallible and universal principles) (Muckelbauer, 2008). Of the two approaches, entrepreneurial practice is more closely aligned with the former, being likewise contingent (van Gelderen & Masurel, 2012) and based on control rather than prediction (Van Gelderen & Masurel, 2012; Sarasvathy, 2001).

Second, taking a broader understanding of rhetoric – one informed by all the post-xisms that have informed the discipline since the latter half of the twentieth century – gestures at the intercept point between entrepreneurship and art as actualizations of virtual breaks in their respective (and interdependent) matrices of intelligibility; the former economic and the latter aesthetic. That is, entrepreneurship and art, according to the rhetorical reading, both emerge from fissures or contradictions in their respective semiotic systems and subsequently alter or expand what is possible within their domains. To clarify, not all artmaking is entrepreneurship and vice-versa: they vary in content and expression and thus have good reasons to remain separate constructs. Rather, there are rather similar processes underlying each, and areas of overlap that offer heuristic illustrations of the phenomenon of arts entrepreneurship.

For both Becker (1983/2008) and White (2019), revolutionary change and the creation of new art worlds are each fundamentally social – and persuasive – activities. "To understand the birth of new art worlds," Becker writes, "...we need to understand, not the genesis of innovations, but rather the process of mobilizing people to join in a cooperative activity on a regular basis" (310-311). Revolution occurs in an art world when its organizational and ideological operations are successfully attacked. This requires coordinated efforts – an organizational attack – to redirect value, capital, and power according to an alternative model.

The social structures and aesthetic beliefs of an art world are facilitated within a "grid of intelligibility" (Biesecker, 1992). This matrix of what is possible to do and to articulate is a product of discourse, a set of signifying practices including taken for granted assumptions, criteria for selection, and objects of interest. Discourse simultaneously interprets and informs material practices (this is the process of social construction), and the combined ouroboric construction constitutes the matrix of intelligibility, which both facilitates and constrains all possible action. Drawing on the work of Michel Foucault, Biesecker explains that this matrix necessarily encloses all practices that it pertains to, but inevitably holds fissures – breaks, potential reversals, glitches – which the entrepreneur explores and acts within toward a desired effect. As Becker notes, this is not necessarily revolutionary, as most who engage in this sort of construction do not have lasting material influence, whether by choice or by circumstance. However, under particular choices and circumstances (including effective mobilization and offering a sustainable alternative [White, 2019]), the fissure is torn beyond the point of repair and new matrices must be imposed to continue making sense.

Biesecker makes clear that there is no outside to this matrix and it is not possible to simply select a point and begin tearing fissures. An acceptable metaphor might be a glitch, where the discourse (be it the signifying practices of a society or of a machine) has gaps which do not exist in actuality until created, though their creation was allowed by the code all along. After this the metaphor breaks down somewhat, but sufficient expansion of this new set of discursive practices will resonate across the art world and alter it according to new rules. These new rules, likewise, allow for new glitches.

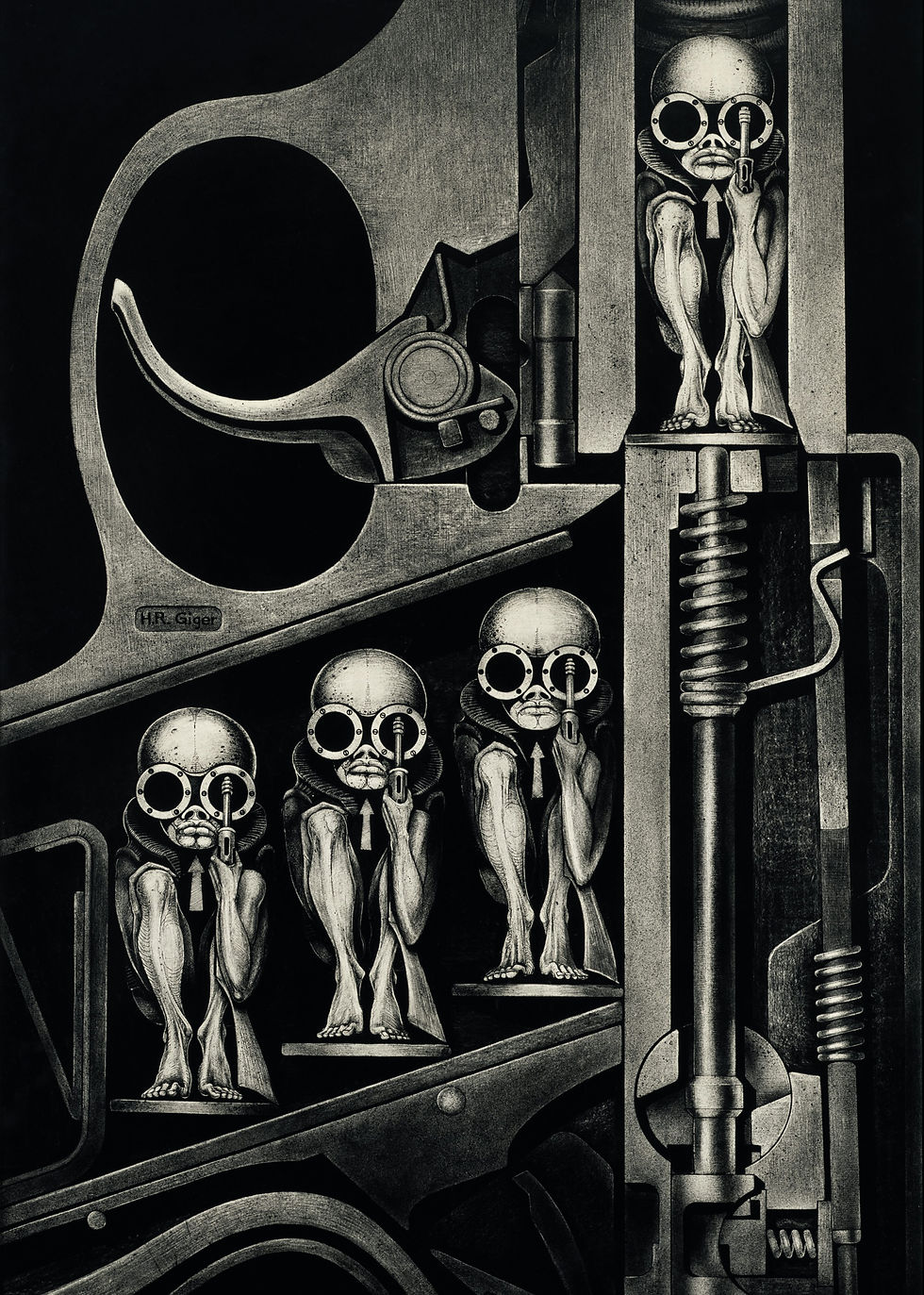

In unfortunately but necessarily brief analysis that follows, I apply rhetorical criticism to the first wave of Industrial Music in the late '70s and early '80s in order to articulate how arts entrepreneurs employed rhetorical tactics of information, attention, and sound itself, using them as tools to engage in emancipatory entrepreneurship. Artists associated with Industrial Music used the format of the pop band to fight what William Burroughs called the “Information War,” disseminating counter-information in the form of music, lyrics, literature, and visuals. These and other modes operated in conjunction (or disjunction) to attack conventions in pop music and Fine Art alongside the hegemonic political-economic discourses and the material practices of art experience that they are symptomatic of.

Industrial Music offers a compelling illustration of these concepts for a number of reasons. First, their explicit objectives allow this study to control for intention and focus strictly on effects. Second, early Industrial artists were driven largely by the emancipatory aims that characterize entrepreneurs in general (and artist-entrepreneurs in particular), such as "desires for autonomy, to express creativity for its own sake, to pursue innovation, and to be one's own boss" (Baker & Pollock, 2007, p. 300). This reflects a broader tendency among artist-entrepreneurs particularly (Chang & Wyszomirski, 2015; Essig, 2015). Finally, Industrial Music, despite its characterization as a musical genre, originally manifested as a convergence of music, performance art and visual arts. This allows me to apply a multimodal rhetorical analysis while attending to the variances and overlaps between the modalities so that artists studying entrepreneurship may relate and draw on their own understandings as resources. In an effort to maintain focus without losing perspective, I attend primarily to the bands Throbbing Gristle and Einstürzende Neubauten, two pioneering industrial acts who represent just some of Industrial Music’s stylistic and cultural diversity.

A Genealogy of Industrial

In his 1983 epitaph to Industrial culture, Jon Savage described Industrial Music as an intervention into the dialogue between avant-garde and pop (Savage, 1983). Industrial Music arose out of the factory refuse of a suddenly and viciously commercialized punk rock, the revolutionary fervor of the former having lost its power and given way to the eternal droning of machinic noise, an icon for the society of control. Scholars traditionally trace the genealogy of Industrial Music to Italian Futurist composers like Pratella and Russolo (Duguid, 1995; Reed, 2015). Catalyzed by Filippo Marinetti's call to arms in 1909, the Futurists sought beauty in progress and its markers: industry, speed, and war. Futurist composers rejected traditional constraints like the twelve-tone system and conventions of melody and harmony, and instead built acoustic noise-making machines, called intonarumori. There were several varieties of these machines, but they all used unconventional methods to emulate or recreate the sounds of industrial machinery that defined the soundscape of early twentieth century Europe.

The forward momentum of Futurism was staggered during World War II, through which Marinetti and other Futurists aligned themselves with the progressive vision of fascism, and after which both state and popular support quickly dwindled. German experimental rock group (sometimes retroactively described as proto-industrial) Kraftwerk represents an important step between Futurism and industrial music, as they were "among the first to reintroduce retrotechnological images tainted by Nazism," (Monroe, 2005, p. 184) and "the first successful artists to incorporate representations of industrial sounds into nonacademic electronic music" (p. 256). While Kraftwerk may have been satisfied in reclaiming a technological identity, their Industrial successors – facing the decay of industrial areas under a burgeoning neoliberalism – held a much deeper cynicism toward technology, progress, and movement. In Industrial Music, movement becomes circular and repetitive, progress becomes meaningless, and technology is a force of social and psychological discipline and control. Here the profound influence of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin (both personal correspondents of Genesis P-Orridge, lead vocalist of the canonical genre codifier Throbbing Gristle) begins to emerge, including philosophies of control as well as methods for emancipation, like the cut-up technique, which would be utilized for musical composition in the form of tape loops and sampling. The intention behind Burroughs' method – to bypass grammatical constructs imposed on the human mind by external forces – can be seen at work in the form of glitches and circuit-bending. "By challenging the capacity of the machine to operate, musicians bypass having to question whether their own reinterpretations and appropriations of technology are merely part of an even larger hidden control mechanism" (Reed, 2015, p. 39).

Beyond these two seminal predecessors, the web of influence becomes increasingly complex. Amid a cultural wasteland, the diverse collection of fiercely independent first generation Industrialists show no fidelity to genre, medium, or discipline in citing influences. Dada (especially Duchamp) and musique concrète (including Cage and the Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrète) are frequently referenced, as are experimental rock bands like the Velvet Underground, the Mothers of Invention, and Captain Beefheart. Artists like SPK draw from Post-Structuralist and Jungian theoretical traditions, while P-Orridge was heavily invested in occultism and the work of Alistair Crowley. Since the logic of the machine that inspired the Futurists had been disenchanted and its influence more thoroughly interrogated, it became necessary to explore this logic across mediums, with a critical ambivalence, and, importantly, in relation to the human body and embodied experience.

Savage helpfully outlines five ideas that underlie industrial culture, which offer an obvious starting point for this analysis. The first is organizational autonomy, an ethos voluntarily sustained by the construction of a DIY culture and communicated through both ideological language and production trends. Access to information is a central concern in the Information War1, a term borrowed from William S. Burroughs. Counter-information, including literature and commentary on philosophy and social theory, was often disseminated through extra-musical elements. Despite this, it was the music that bridged the gap between the intellectual/avant-garde and the popular audiences that needed to hear the message – music was employed explicitly as a persuasive force in the information war. The use of synthesizers and anti-music characterizes industrial music, but only comprises part of a wider variety of deliberate tactics by which industrial artists drew an audience while attacking the aesthetic conventions of both pop and Art music. The final principle is shock tactics, which served not only to call attention and generate buzz, but as a means to shock audiences out of accustomed habits. Guided by these largely unspoken principles, the Industrial movement consisted of artists who engaged simultaneously in entrepreneurial art and business practices.

Industrial Strategies

1. Organizational Autonomy

The principle of organizational autonomy emerged to address a number of practical concerns, like funding niche (often deliberately inaccessible) music projects and exercising control over artistic expression. At the same time, maintaining autonomy was an ethical appeal to the community's anti-authority and anti-capitalist sentiments, as well as an incentive to innovate and move past the "tainted and unnecessary" model of major label distribution (Savage, 1983). DIY tactics like self-production, self-distribution, and using self-made, found, pawned, or stolen instruments were encouraged through the scene's DIY discourse – grounded not so much in working-class solidarity, as was the case with punk music, but in a philosophical understanding of the possibilities of artistic creation freed from the (mutually reinforcing) restraints of traditional notions of aesthetic judgement and global flows of capital (Reed, 2015). These sorts of economic-aesthetic tactics can be traced to the Fluxus movement and its leader, the "avant-garde entrepreneur” George Maciunas, whose efforts to desacralize and demonetize art through mass production let him to attempt “to establish a world-wide network of Fluxshops and Flux Mail-order Warehouses” (Ford, 1999, p. 3.11).

By nearly all accounts, Throbbing Gristle (TG) was the first Industrial band, and their independent record label Industrial Records became the genre’s namesake (Reed, 2015). TG can be understood both as a band and as one stage in an evolving and branching series of radical performance art groups. Bassist and vocalist Genesis P-Orridge, guitarist and vocalist Cosey Fanni Tutti, tape manipulator and graphic designer Peter "Sleazy" Christopherson, and synthesist and sound/light technician Chris Carter first met as members of the music and performance art troupe COUM Transmissions, and TG itself would eventually split into video/music group Psychic TV and band Chris & Cosey (among other side projects). [4] Like many of their peers, TG operated according to an effectual logic, taking amateurism and DIY-ism as axiomatic and exploring possible effects (Sarasvathy, 2001).

Given their antagonistic and evidently unmarketable artistic product, TG put their existing skills and resources to work founding Industrial Records. "Through hard-earned connections in governmental arts councils, the entertainment business, and post-hippie subculture," writes Reed, "Throbbing Gristle's members organized a financial support system that allowed them shortly after their official formation to launch the label" (p. 73). TG started production on their debut full-length album Second Annual Report in 1977, recording on a budget of £700 using inexpensive (largely second hand or obsolete) equipment (Ford, 1999).

For TG and the Industrial movement at large, such an entrepreneurial DIY approach was not just necessary, but desirable for its counter-aesthetic and counter-economic effects. Mark Dery (1996) observes Industrial artists are "engaged in the inherently political activity of expropriating technology from the scientists and CEOs, policymakers and opinion-shapers who have traditionally determined the applications, availability and evolution of the devices that, more and more, shape our lives" (p. 15). Karen Collins (2005), discussing the common ethos of Industrial and Cyberpunk, argues that "by appropriating the outsider as hero, and celebrating difference, the authors and artists make one more strike against the mass-culture society presented in the narratives" (p. 172). On the aesthetic motivations, P-Orridge explained that the band wanted the recording “to be unprecious in every way except thee [sic – more on the spelling later] information implicit in material and in our choice of sound, and its rarity as an object." (qtd. in Ford, p. 7.22).

Such entrepreneurial tactics, then, in addition to affording artists emancipatory control of their artwork and organization, themselves acted as a persuasive force; an economic argument and mobilization against the dominant neoliberal order and popular aesthetic paradigms, and for the consumption of art and music outside traditional channels – an argument that resulted (albeit briefly) in the construction of an art world that operated according to a different set of rules. This represents, in Becker's conception of revolutionary change in an art world, an organizational line of attack on existing economic-material practices (2008). Through their distribution and production practices, Industrial Records and other independent labels in the Industrial scene (including fellow British labels Mute and Some Bizzare, as well as Chicago's Wax Trax!), diverted flows of capital away from major labels and to a close-knit community of likeminded artists.

2. Access to Information / Extra-Musical Elements

Aside from the economic rhetoric of entrepreneurship and DIY, TG and Industrial Records codified what would become the archetypal image and aesthetic-rhetorical tactics of Industrial music. These tactics were first and foremost invested in what Burroughs called the information war. For TG, music was a means to an end, and that end was revealing and combating the control machines (likewise Burroughs’ terminology) that influence thought and behavior (Savage).

TG and other Industrial artists adopted a guerrilla strategy to the information war, eschewing conventional ways of distributing information (this is in itself a strategic move, as these conventions are informed by the systems they hoped to undermine). Album liner notes became means of pointing listeners to theorists, writers, spiritualists, and other bands which they may not have have encountered otherwise. This practice was exemplified by the French record label Sordide Sentimental, who issued records by a diverse selection of artists (including TG and Joy Division) packaged with artwork and philosophical texts, encouraging critical intellectual as well as aesthetic engagement. Co-founder Yves Von Bontee, who authored many of these texts discusses the importance of enthymeme as a rhetorical technique and a mode of reasoning:

"When I am writing, most of the time I try to stop in the middle of a sentence, just to try to oblige people to continue the sentence with their own imagination, and to work with the meaning. I hate people only wanting to receive, who don't want to give anything, who don't want to participate." (qtd. in Vale & Juno, 1983, p. 85)

The band Nurse With Wound offers another example of the variety of information that could be disseminated, including in the packaging of their first two releases a list of musical influences from the contemporary (TG, Cabaret Voltaire) to the canonical (Velvet Underground, John Cage) to a collection of virtually unknown artists. This list offers what might be called, to adapt Deleuze and Guattari’s terminology, a minor musicology.

For TG and P-Orridge in particular, language itself serves an important function in shaping thought, something that reflects in his extra-musical writing. [5] Following his hero and mentor William Burroughs, P-Orridge sought ways to undermine linguistic processes in order to liberate thought and expression from the power structures in which language is inevitably bound. Most notable is the use of unconventional spelling and terminology that he developed throughout his career. This can be illustrated in an essay on Burroughs’ and Gysin’s cut-up method, a technique he performatively demonstrates using the very function of language:

"In culture thee Cut-up is still a modification of, or alternate, language. It can reveal, describe and measure Control[...] Thee aim is reclamation of self-determination, conscious and unconscious, to the Individual. Thee result is to neutralise and challenge thee essence of social control" (P-Orridge, qtd. in Partridge, 2014, p. 201).

Partridge (2014) asserts that these "odd spellings and grammatical constructions are intended to challenge thought and ways of reading; they provide a challenge to the ways in which we have learned to think; our angle of vision is bent during the process of reading; words are given, he argues, 'added levels of meaning'" (p. 201). This is the rhetorical technique of defamiliarization, which was likely first articulated when Aristotle (c. 325/2007) observed that "To deviate [from prevailing usage] makes language seem more elevated [...] As a result, one should make the language unfamiliar" (p. 198). Defamiliarization – or, following Shklovsky (1917/2016), ostranenie – involves the manipulation of language in order to cast a familiar concept in a new way (Iglesias-Crespo, 2021; Kennedy’s notes on Aristotle, 2007). These and P-Orridge's other unconventional and suggestive spellings play with signifying chains, evoking interesting new connections between words and allowing for new affective resonances: in place of “the,” “thee” is an antiquated but intimate way to address a noun; in place of “realize”, “real-eyes” casts cognitive understanding as a material-sensory phenomenon; in place of “alchemical” and “alter”, “all-chemical” and “altar” operate in different directions to blur the lines between the rational-scientific and the magical (rather, "magickal" – though in this case P-Orridge is evoking Alistair Crowley). Of course, these are only subjective readings of deliberately open-ended language play, and by ascribing them particular meanings I defeat the purpose, which is to allow connotations to proliferate and therefore bypass built-in interpretation and return control of language to the individual.

3. Anti-Music

Operating in tandem with their organizational attack, Industrial artists' approach to music represents an essential aesthetic dimension of the revolutionary change they hoped to effectuate. Industrial music reflects an incredible stylistic diversity, a phenomenon largely traceable to its profound concern for locality. The importance of locality to what so quickly became a global phenomenon (by 1980 – four years after TG's debut cassette release – there were major artists active in at least the UK, US, Germany, Sweden, Australia and Slovenia) is best understood as artists reacting to localized manifestations of globalized forces in similarly localized ways. The shadow of WWII, the cultural tensions of the Cold War, and the expanding hegemony of neoliberalism all loomed over a plurality of post-industrial landscapes, but each landscape bore unique scars on its own unique cultural body, and therefore facilitated its own types of Industrial expression. This can be felt and heard sonically, with artists sampling the material and cultural artifacts that surrounded them, as well as singing (or speaking or yelling) largely in their local dialect.

In few places is this localism better expressed than in the music of Einstürzende Neubauten. Hailing from Berlin, Einstürzende Neubauten (EN) was incubated in a complex post-war cultural environment. State enforced guilt, foreign occupation, and a war-torn cityscape clashed with a vibrant artistic community bolstered by inexpensive housing and extensive squatting communities, as well as robust arts initiatives meant to compete with Soviet East Germany (Reed). EN's defining musical characteristic is their reliance on found objects for percussion and texture, a practice that reportedly originated in squatters pounding out rhythms on the city's metal barricades (Reed). Their sound was built from the detritus of the city itself; scraping and hammering on metal beams, shattering glass, beating a shopping cart across the stage with a metal rod, etc. Many of these "instruments" were found or stolen from the city's streets. More complicated instruments were built from similarly found and stolen materials. The overall effect is highly material, manifesting in a real context signifying not through symbols or abstraction but through the physical resonant (in this case, both sonically resonant and having a moving affect) properties of the artifacts themselves (Blair, 1999; Dickson, 1999; Zagacki & Gallagher, 2009). Berlin’s political importance during and after WWII, in many ways, vastly overshadowed its real existence. “[F]or commentators past and present,” writes Birdsall, “Berlin is often an abstraction, an idea or a surface as much as a lived, material city” (2012, p. 13). EN’s percussive soundscapes do not symbolize Berlin, and their music does not evoke Berlin. The soundscape is Berlin, and the music berates the listener with the material resonance of the city itself, cutting through such symbolic abstractions.

Also of note is frontman Blixa Bargeld's vocal delivery. A style that began as fairly straightforward shouting was soon refined, with 1985's Halber Mensch, into a combination of singing, whispering, shouting, and inhuman screeching, inspired in part by the raw, chaotic vocalizations of Antonin Artaud (Carpenter, 2017). Like EN's percussion section (and likewise going against the general trend in Industrial music), Bargeld's voice diverges from the standard tropes of Industrial music in how little processing is to it, drawing attention to the pure sounds of the German language at its outer limits. It is no surprise that he, like many of his Industrial-minded countrymen, chose to sing (and yell and hiss and croak) in German at a time when most pop musicians preferred to sing in the gentler and less culturally loaded language of English. Bargeld and EN sought specifically to examine and problematize the relationship between their mother tongue (just like the city itself) and Nazism, emphasizing the guttural consonants, open vowels, trochee rhythms that characterize the language in an attempt to reclaim it and build it a better legacy.

EN's raw sonic-material rhetoric can be contrasted with the synthesized and manipulated music of TG. TG was more interested in the physical force of sound as material, at least one point playing "so loud that the audience could feel the air pushing against their bodies to the point of causing physical pain, an effect that was augmented by the use of extreme registers and long blasts of mechanical sounds" (Hanley, 2011, p. 198). At sufficiently high volumes and sufficiently low frequencies, the vibrational force that sounds exerts on the body has disorienting and defamiliarizing effects (Jasen, 2016). As auditory, tactile, proprioceptive, and visual inputs slightly contradict each other, extreme sound has been shown to induce stress and motion sickness and to interrupt cognitive processes (Leventhall, Pelmear, & Benton, 2003). Consider TG's disturbing visual imagery and their use of enargaeia – i.e. vivid and evocative description of a visual experience (Webb 2009) – in handouts like the following from their 1976 debut:

"Imagine walking down blurred streets of havoc, post-civilisation, stray dogs eating refuse, wind creeping across tendrils. It's 1984. The only reality is waiting. Mortal. It's the death factory society, hypnotic mechanical grinding, music of hopelessness. Film music to cover the holocaust. Tantra of the subliminal, word falling, photo falling. In a nostalgia for feeling totally sterile endless tribal music. Thee tribe of mutations, street gangs lobotomised in the Death Factory. It never ends. TV Children trying to prepare themselves, meditating on, cease to exist." (Ford, 1999, p. 6.17)

The combined, multimodal experience not only serves to disorient the audience, but brings in enargaeic depiction to surround the listener in a dystopian landscape that becomes the locus of their anxiety. Audiences reportedly found the performance "powerful" and "difficult" (p. 6.16), attesting to the resulting effect and, perhaps, to a new and more skeptical view of the world around them.

// section on Cabaret Voltaire

Back to the dichotomy of noise-based to rhythm-based strands of Industrial Music – CV represents the latter style

Danceability

—Whereas EN and TG reflected avant-garde modernist sensibilities (Hanley, 2011; Carpenter, 2017), CV's more thorough (and danceable) incorporation of pop into noise foreshadows the "postmodernist manipulation of musical and visual signifiers" (Carpenter, p. 151) that would eventually dominate industrial music.

—"Nag Nag Nag" (Reed, p. 64; Jasen on the physio-logic of the drum machine)

Remediated voice

—Barthes rerun ft. Neumark, Gibson, & van Leeuwen

—Industrial Music, CV's output especially, works in opposition to sung language, which has typically held a dominant position in musical rhetoric (Rickert, 2006). Distorted words are drowned out by equally distorted music, challenging the hegemony of language (logos, the Word) and instead inviting the listener to dwell in affect and ambiguity. Lyrics, which were often only determinable from liner notes anyway, fall under the category of extra-musical elements that were essential to spreading the industrial ethos. Language carries information, and information is a mechanism of control, while music acts directly on the body.

4. Shock Tactics

The term “shock rock” has been applied to popular artists from Screamin’ Jay Hawkins in the ‘50s to contemporary Industrial Rock acts like Marilyn Manson and Rammstein (Bryant, 2014). The shock tactics of early Industrial Musicians like Throbbing Gristle, however, are more closely linked with the radical performance art movements of the 1960s and ‘70s, particularly Fluxus and the controversial antics of the Viennese Actionists, both of whom profoundly influenced TG in their early work as COUM Transmissions. Whereas Fluxus was influential for the anti-art aesthetic and business model, COUM were attracted to the Actionists for their "use of 'shock tactics’ to break down repression," and "their commitment to deliberately confronting the consensus morality of their society” (Ford, 1999, 3.17).

The two sentiments were gradually reconciled with a series of performance/conceptual Art pieces that took place at the transition point between COUM and TG in 1976, culminating in the infamous Prostitution exhibition. In an article published in the Art Journal Studio International, P-Orridge and Christopherson asserted that Tutti’s past work modeling for pornographic magazines was in fact performance art – a calculated and covert attempt to disseminate en masse what was, according to authorial intent, artistic nudes, the culmination of a Fluxus-inspired effort to destroy the value of Art (P-Orridge & Christopherson, 1976). To drive home the message, these photographs were then cut from magazines and framed as part of an exhibition at the ICA Arts Center later that year, alongside props from past performances. This exhibit, titled Prostitution, sparked moral outrage, leading MP Nicholas Fairbairn to label the group as “wreckers of civilization.” Over 100 newspaper and magazine articles were published discussing the exhibition and its fallout, and, as the final stage of the project, cuttings from these articles were likewise framed and exhibited (Ford, 1999).

The combined final product put on display both the “prostitution” of artists who operate under the funding (and control) of public institutions and therefore (according to the media discourse) must serve the interests of the state, as well as the literal prostitution that artists often resort to in order to sustain their artistic careers, all while challenging notions of high versus low art (Ford, 1999). [6] Most pertinently, however, this exhibit functioned as a test for strategies of rhetorical circulation (Edbauer, 2005; Gries, 2015). Both the guerrilla manufacturing of Art through pornographic magazines and then COUM’s quickness to seize on the flurry of media coverage which soon turned P-Orridge and Tutti into household names illustrate ways in which semiotic meanings and rhetorical effects change as artifacts are reproduced, transform, and move through their environments. As a result of this “test” COUM was able to recognize the limitations of state and institutional support (ICA soon lost public funding as a result of the controversy), so COUM’s next step was to harness power of the spectacle through a mode that would both reach more people and provide a sustainable income – popular music.

Throbbing Gristle (thankfully) did not make an effort to surpass their predecessors in extremity and grotesqueness. They had come to understood the dynamics of the Information War better than the Actionists or Fluxus, and their project was not to evolve qualitatively, but to expand quantitatively. Shock tactics became an essential part of Industrial Music’s vocabulary, constituting both a means of psychic liberation from conventional cultural codes and “a time honored technique to make sure what you have to say gets noticed” (Savage, 1983, p. 5). Some of these techniques were familiar; TG and Slovenian group Laibach subverted totalitarian and fascist imagery in a way not dissimilar to early punks’ appropriation of the swastika, as a guerrilla semiotics that seeks to strategically disrupt the link between the signifier and signified (Eco, 1983/1986). Whereas, for punks, this move was motivated by a profound nihilism, Industrial artists followed in COUM’s footsteps by playing with new associations and provoking their audience to think critically about the media messages they encounter. For instance, Industrial Records’ logo could easily be mistaken for a generic image of an English industrial town, were it not for liner notes specifying that it is a photograph of the Auschwitz concentration camp (Ford, 1999). TG and following bands garnered both attraction via controversy and retention via their radical, subversive brands, yet it remains impossible to separate what might cynically be considered “publicity stunts” from their avant-garde aesthetics and emancipatory philosophical beliefs.

Discussion: Bricolage and Rhetorical Invention

Because of its use of DIY tactics and creative manipulation of cultural codes, Industrial Music represents an exemplary case of entrepreneurial bricolage. Structuralist anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss popularized this term – which, in its mundane sense, is comparable to “DIY" or "tinkering" – to explain how myths take existing signs and repurpose them in creative ways toward practical ends (1962/1966). Bricolage is defined as making do with "whatever is at hand" (p. 17). The bricoleur employs a diverse array of means present in any given situation, finding diverse uses for these resources (and discarding or repurposing them when necessary) based on one's particular objective. There are then two ways to understand bricolage, or more accurately two dimensions to the process of bricolage. In addition to the original sense of the word as concerned with physical material, Lévi-Strauss introduced "intellectual bricolage" as finding creative uses for undesirable, discarded, or unconventional conceptual resources, including signs and stories (as in myth) as well as theoretical concepts (as in his own anthropological research). Intellectual bricolage has since seen widespread usage across multiple disciplines, including rhetoric studies, where both material and intellectual bricolage are understood as methods of rhetorical invention to find creative uses for the existing means of persuasion, including doxa, cultural codes and referents, or even media artifacts (as remix) (Jasinski, 2001; Sturken & Cartwright, 2018). Intellectual bricolage in particular has been used to describe the theoretical work of rhetorical critics, who necessarily operate within an inherited discourse and therefore are charged with finding new applications for disparate or discarded concepts (Charland, 1991). The ends of previous efforts then become the means for solving new problems.

Bricolage as both a material and a conceptual practice has been forwarded as a model for how entrepreneurs put unrecognized, unconventional, or otherwise unutilized resources to heterogenous uses in resource-poor environments (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Di Domenico, Haugh, and Tracey’s (2010) framework of social bricolage outlines three principles of bricolage in general: making do, refusal to be constrained by limitation, and improvisation; as well as three additional characteristics of social bricolage in particular: creation of social value, stakeholder participation, and persuasion. Preece (2014) found this to be a productive model for Arts Entrepreneurship, arguing that based on the "resource constraints confronting the arts, [social bricolage] is arguably the most viable route to start-up success” (p. 32).

This study supports Preece’s assessment, while elucidating the nature and effect of such bricolage based on insights from rhetorical theory. Motivated by the need for organizational autonomy and restrained by their niche market, Industrial artists engaged in a number of both material and intellectual tactics of social bricolage. Practices of "making do" included low-budget self-production and self-distribution (often taking place in musicians' homes or run down/abandoned buildings), as well as using self-made, found, pawned, or stolen instruments. These practices were necessitated by the socio-economic disadvantages that numerous artists faced as a result of the globalization of industry and the prolonged aftermath of World War II (not to mention the niche market for their challenging avant-garde music), but also served as economic arguments against traditional economic channels and aesthetic arguments for experimental and lo-fi approaches to music. “Improvisation” can be seen most generally in the creation of uniquely engaging multimodal artistic products by harnessing diverse artistic backgrounds. For a specific example, one might point to how the artists that comprised TG continually assessed the media environment of their audience, motivating their evolution from performance art group to experimental anti-rock band before splintering into an array of multimedia-oriented side projects.

The type(s) of social value created differentiate Arts Entrepreneurship from social entrepreneurship more generally. "While the arts do not address social ills or the disenfranchised directly," writes Preece, their unique social value "can encourage social cohesion, artistic expression and community health across the board” (p. 30). Social cohesion can be identified in the creation and popularization (and, in the 1990s, mainstream explosion) of an Industrial subculture, itself a bricolage of goth, punk, fetish, and militant aesthetics. Artistic expression represents perhaps the most radical innovation, and includes, for instance, the conceptual bricolage of TG's cut-up tape loop (new uses for media artifacts drawn from a stockpile of cultural resources) and P-Orridge's defamiliarizing writing style (new connotations drawn from the existing structures of language), as well as EN's material rhetorics of locality (new ways of expression drawn from the material environment). While the likes of Nicholas Fairbairn might disagree (and though most Industrial Musicians would likely contest the notion of one totalizing notion of "community health”), it's difficult to argue that TG and other politically-minded Industrial artists intended to effect positive change. Their use of defamiliarization and shock tactics represented an explicit attempt to shake audiences out of aesthetic and discursive habits, and therefore liberate them from institutional control and restore a degree of self-determination.

The persuasive dimensions of social bricolage – which are of particular concern for this study – are largely inseparable from the creation of value in the case of Industrial Music. Invigorated by the discourse of the Information War and informed by their early days performing Fluxus-style “happenings,” Throbbing Gristle (as well as their industrial kin) synthesized art and marketing into something that was understood as authentic and radical while serving simultaneously as a powerful advertising machine. This was made possible through TG's own understanding of their work as fundamentally political and their end goal, therefore, as persuasion.

When artistic and entrepreneurial action is reframed this way through rhetorical notions of effect, movement, and resonance (rather than, say, aesthetics or profit), then marketing, branding, and Art can mutually reinforce each other in such a way that appeals to even those audiences most wary of the intersection between business and art. This synergy between artistic, (counter-)economic, and (counter-)discursive practice might be seen as a higher order conceptual bricolage, wherein all available fields offer an array of resources for achieving a desired effect. For Arts Entrepreneurship educators, then, finding ways to connect business practice and art through rhetorical terms is one of several transdisciplinary methods to teach entrepreneurial skills to those who remain “uneasy with entrepreneurship defined exclusively as the creation of material wealth” (Beckman & Cherwitz, 2009, p. 21). Simultaneously, it suggests particular attention to the "creation of social value" element of the social bricolage framework while tethering it to a more nuanced understanding of “persuasion.” That is, Art (the social value) is persuasive in the sense that it is moves you.

Intellectual bricolage through appropriating and repurposing interdisciplinary concepts to specialized ends is itself characteristic of Arts Entrepreneurship as a scholarly field. It is by now the scholarly consensus that the unique characteristics of the arts industries mean an entrepreneurship curriculum cannot be imported directly. Concepts like the value proposition or even the notion of bricolage itself are imperfect tools when applied to the Arts, but they can be repurposed as the value statement (Bryan & Harris, 2015) and social bricolage (Preece, 2014). If the primary goal is effect, then – like the early Industrial artists – Arts Entrepreneurship educators should be unafraid of improvising with a diverse array of concepts in order to reconcile students’ artistic and financial interests and empower them to find creative uses for their own skillsets. One such tactic is to follow students’ artistic interests in order to engage with their philosophical underpinnings and then their rhetorical possibilities. This can be seen at work in TG’s relationship with William Burroughs, from whom they drew artistic inspiration and eventually a specific philosophy and strategy for combining artistic and business practices into a cohesive whole.

In line with Beckman & Cherwitz (2009), then, I would argue for the continued importance of this sort of intellectual bricolage in order to reconcile and integrate entrepreneurial thinking with liberal arts disciplines like philosophy, rhetoric, and the Arts. By recognizing the contingency of all concepts and seeking out new uses for old concepts, this understanding of bricolage encourages a self-reflexive understanding of entrepreneurial thinking – a philosophical entrepreneurship – to underlie entrepreneurial research and practice.

Conclusion: Industrial Metaphors

If rhetoric is defined by responses and effects, then what can be said of the lasting effects of the first wave of Industrial Music? Bargeld, who, in 1980, prophesied "two years to the apocalypse" (qtd. in Reed, p. 91), might have failed to predict a full-scale societal collapse, but, according to Savage, he wouldn’t have been far off in predicting the inevitable self-destruction of Industrial music. He cites as inspiration Walter Benjamin's description of the Destructive Character (ShiAkaShi, 2007), who "knows only one watchword: make room" and who "has few needs[...] the least of them is to know what will replace what has been destroyed" (Benjamin 1931/2019, p. 301).

There are creative rhetorics, which use vivid and theatric depiction to instill wonder and open possibility (see Gallagher, Martin, & Ma, 2011), but there are also destructive rhetorics, which use the same principles to illuminate horror and contradiction, throw the familiar into unfamiliar framing, or otherwise break down concepts. The two work in tandem to motivate new forms of social organization, a sentiment which is echoed in both Becker’s (1983/2008) work on the sociology of art and Guilford’s (1950) landmark essay on the psychology of creativity.

The quick death of Industrial music did not indicate failure. Rather, Industrial's short lifespan is indicative of its profound success: systems of power that controlled music production, distribution, consumption, and aesthetic enjoyment had all been dealt crippling blows. These are still felt today in the form of Industrial Body Music and derivative genres, the proliferation of sampling in genres from hip-hop to heavy metal, and digital-age DIY movements. However, the war metaphors that pervaded Industrial Music's early discourse are limited in what they allow. [7] By 1983 it was time to leave the medium of music to be rebuilt with more constructive rhetorics (like “assimilation” during the second generation [Reed, 2015; Hanley, 2011]) and time for the Industrial war machine to move on to the next front:

"The apocalyptic feelings of 1977 and 1978 have burned out: what has replaced them is a grimmer determination to translate that desperation into positive action, in our slide to the depths of decline. The context has shifted: pop is no longer important; temporarily, television is. It is there that the next round in the Information War is being fought" (Savage, 1983, p. 5, emphasis in original).

Savage's language perfectly reflects an understanding of Industrial as organized attack against hegemonic social, economic, and aesthetic systems, and further one which demands the assessment and utilization of heterogenous economic and aesthetic resources.

Notes

[1] Despite the allure of Schumpeter’s “industrial mutation” metaphor, throughout this study I rely on Becker’s conceptualization of revolutionary enterprise (as ideological and organizational attack on the systems of an art world) over Schumpeter’s (as Creative Destruction) due to the greater recency and specific Arts-orientation of the former.

[2] Rhetoric as persuasion has not gone unchallenged, e.g. by Foss & Griffin, 1995, but I feel such a challenge unhelpfully collapses rhetoric into the field of communication.

[3] See literature reviews of rhetoric in management (Hartelius & Browning, 2008), marketing (Miles & Nilsson, 2018), and entrepreneurship (Spinuzzi, 2017).

[4] In 2003, P-Orridge and spouse Jaqueline Breyer began the Pandrogyne project, indenting to apply literary cut-up techniques to their own bodies in an effort to liberate consciousness from gender identity and from the individualized body. They became – through behavioral mimicry as well as surgical modification – identical aspects of the same person, taking the shared surname Breyer P-Orridge and using plural pronouns. Following Reed, I retain masculine singular pronouns when referring to P-Orridge before the advent of this project, both for clarity and in the spirit of the project as a performative invention (rather than correction or discovery) of the self.

[5] This notion (linguistic relativity, also known as the "soft" version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis) likewise has wide support in cognitive sciences. See, e.g. Lucy (2015).

[6] It’s worth noting that for Tutti, personally, the exhibition served as a reclamation of her body and a reconciliation between her financially-motivated modeling work and her position as an artist-entrepreneur (Tutti, 2017)

[7] On the significance of metaphors in facilitating different kinds of thinking, cognitive science once again reinforces the work of rhetorical theory. See Thibodeau & Boroditsky 2013; 2015

References

Aldrich, H. E. (2005). Entrepreneurship. In N. J. Smelser & R. Swedberg (Eds.), Handbook of economic sociology (2nd ed., pp. 451-477). Princeton University Press.

Aristotle. (2007). On rhetoric: A theory of civic discourse. (G. A. Kennedy, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published c. 325 BCE).

Baker, T. & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329-366.

Baker, T. & Pollock, T. G. (2007). Making the marriage work: The benefits of strategy's takeover of entrepreneurship for strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5(3), 297-312.

Barnett, S., & Boyle, C. (2016). Introduction: Rhetorical ontology, or, how to do things with things. In Barnett, S., & Boyle, C. (Eds.), Rhetoric, through everyday things (pp. 30-41). The University of Alabama Press.

Becker, H. S. (2008) Art worlds, 25th anniversary edition. University of California Press. (Original work published 1983).

Beckman, G. D. (2014). What arts entrepreneurship isn’t. Journal of Arts Entrepreneurship Research 1(1), 3-18.

Beckman, G. D. (2015). Entrepreneuring the aesthetic: Arts entrepreneurship and reconciliation. In T. Baker & F. Welter (Eds.), The Routledge companion to entrepreneurship (pp. 296-308). Routledge.

Beckman, G. D. & Cherwitz, R. (2009). Advancing the authentic: Intellectual entrepreneurship and the role of the business school in fine arts entrepreneurship curriculum design. In E. J. Gatewood, G. P. West, & K. G. Shaver (Eds.) Handbook of University-wide Entrepreneurship Education, (pp. 21-34). Edward Elgar.

Benjamin, W. (2019). The destructive character. In E. F. Jephcott (Ed.), P. Demetz (Trans.), Reflections: Essays, aphorisms, autobiographical writings (pp. 301–303). Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. (Original work published 1931)

Biesecker, B. (1992). Michel Foucault and the question of rhetoric. Philosophy & Rhetoric, 25(4), 351–364.

Birdsall, C. (2012). Nazi soundscapes: Sound, technology and urban space in Germany, 1933-1945. Amsterdam University Press.

Blair, C. (1999). Contemporary U.S. memorial sites as exemplars of rhetoric’s materiality. In J. Selzer & S. Crowley (Eds.), Rhetorical bodies (pp. 16-57). University of Wisconsin Press.

Blair, C., Jeppeson, M. S., Pucci, E. (1991). Public memorializing in postmodernity: The Vietnam veterans memorial as prototype. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 77(3), 263-288.

Bryan, T. S. & Harris, D. (2015). The aesthetic value exchange: A potential framework for the arts entrepreneurship classroom. Journal of Arts Entrepreneurship Education, 1(1), 25-54.

Bryant, T. (2014, June 26). A brief history of shock rock. Louder. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://www.loudersound.com/features/a-brief-history-of-shock-rock.

Callander, A. (2019). Artmaking as entrepreneurship: Effectuation and emancipation in artwork formation. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 8(2), 61–79. https:// doi.org/10.34053/artivate.8.2.4

Charland, M. (1991). Finding a horizon and telos: The challenge to critical rhetoric. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 77, 71-74.

Collins, K. (2005). Dead channel surfing: The commonalities between cyberpunk literature and industrial music. Popular Music, 24(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261143005000401

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper Perennial

Dannreuther, C., & Perren, L. (2015). The rhetoric of power: Entrepreneurship and politics. In T. Baker & F. Welter (Eds.) The Routledge companion to entrepreneurship (pp. 376-390).

Deleuze, G. (2007). What is the creative act? In D. Lapoujade (Ed.), A. Hodges & M. Taormina (Trans.), Two regimes of madness: Texts and interviews 1975-1995 (pp. 312–324). Semiotext(e). (Original work published 1987)

Dery, M. (1996). Escape velocity: Cyberculture at the end of the Century. Grove Press.

Di Domenico, M, Haugh, H. & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681-703.

Dickson, B. (1999). Reading Maternity Materially: The Case of Demi Moore. In J. Selzer & S. Crowley (Eds.), Rhetorical bodies (pp. 297–313). University of Wisconsin Press.

Duguid, B. (1995). A prehistory of Industrial Music. EST. Retrieved November 28, 2021, from http://media.hyperreal.org/zines/est/articles/preindex.html.

Eco, U. (1990). Towards a semiological guerrilla warfare. In W. Weaver (Trans.), Travels in hyperreality (pp. 135–144). Mariner Books. (Original work published 1983)

Edbauer, J. (2005). Unframing models of public distribution: From rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecologies. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 35(4), 5-24.

Essig, L. (2015). Means and Ends: A Theory framework for understanding entrepreneurship in the US arts and culture sector. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 45(4), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2015.1103673

Ford, S. (1999). Wreckers of civilisation: The story of COUM Transmissions & Throbbing Gristle. Black Dog Publishing.

Gries, L. E. (2015). Still life with rhetoric: A new materialist approach for visual rhetorics. Utah State University Press.

Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454.

Guilford, J. P. (1959) Traits of creativity. In H. H. Anderson (Ed.) Creativity and its cultivation (pp. 142-61). Harper & Row.

Hanley, J. (2011). Metal machine music: Technology, noise, and modernism in Industrial Music 1975-1996 [Doctoral dissertation]. Stony Brook University

Hart, J. & Beckman, G. D. (2015). Arts entrepreneurship: You are closer than you think. In C. Svich (Ed.), Innovation in five acts: Strategies for theatre and performance. Theatre Communications Group.

Hartelius, E. J., & Browning, L. D. (2008). The application of rhetorical theory in managerial research. Management Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0893318908318513

Iglesias-Crespo, C. (2021). Energeia as defamiliarization: Reading Aristotle with Shklovsky’s eyes. Journal for the History of Rhetoric, 24(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/26878003.2021.1975465

Jasen, P. C. (2016). Low End Theory: Bass, Bodies and the Materiality of Sonic Experience. Bloomsbury Academic.

Jasinski, J. (2001). Sourcebook on Rhetoric. SAGE.

Leventhall, G., Pelmear, P., & Benton, S. (2003) (rep.). A Review of Published Research on Low Frequency Noise and its Effects. London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Lévi Strauss, C. (1966). The savage mind (unknown trans.). Weidenfeld and Nicolson. (Originally published 1962).

Lucy, J. A. (2015). Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed., pp. 903–906). Elsevier.

Miles, C., & Nilsson, T. (2018). Marketing (as) rhetoric: An introduction. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(15-16), 1259–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2018.1544805

Monroe, A. (2005). Interrogation machine: Laibach and NSK. MIT Press.

Muckelbauer, J. (2008). The future of invention: rhetoric, postmodernism, and the problem of change. State University of New York Press.

Muckelbauer, J. (2016). Implicit paradigms of rhetoric: Aristotelian, cultural, and heliotropic. In Barnett, S., & Boyle, C. (Eds.), Rhetoric, through everyday things (pp. 30-41). The University of Alabama Press.

Partridge, C. (2014). Esoterrorism and the wrecking of civilization: Genesis P-Orridge and the rise of industrial paganism. In D. Weston & A. Bennet (Eds.), Pop pagans: Paganism and popular music. Routledge.

P-Orridge, G. & Christopherson, P. (1976). Annihilating Reality. Studio International, 192(982), 44-48.

Preece, S. (2014). Social bricolage in arts entrepreneurship: Building a jazz society from scratch. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 3(1) 23-34.

Reed, S. A. (2013). Assimilate: A critical history of industrial music. Oxford University Press.

Rickert, T. (2006). Language's Duality and the Rhetorical Problem of Music. In Bizzell, P. (Ed.) Rhetorical Agendas: Political, Ethical, Spiritual.

Rindova, V., Barry, D., & Ketchen, D. J. (2009). Introduction to special topic forum: Entrepreneuring as emancipation. The Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 477– 491. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27760015

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/259121

Savage, J. (1983). Introduction. In V. Vale & A. Juno (Eds.), Industrial culture handbook. RE/Search Publications.

Scherdin, M. & Zander, I. (2011). Art entrepreneurship: an introduction. In Art entrepreneurship (pp. 1-9). Edward Elgar.

Schumpteter, Joseph A. (2003) Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Routledge. (Original work published 1942)

ShiAkaShi. (2009). Einsturzende Neubauten - Sehnsucht. YouTube. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TkASjf8Efss.

Shklovsky, V. (2016). Art as Device. In A. Berlina (Trans.), Viktor Shklovsky: A reader (pp. 73–96). Bloomsbury Academic. (Original work published 1919)

Spinuzzi, C. (2017). Introduction to special issue on the rhetoric of entrepreneurship. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 31(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1050651917695537

Sturken, M. & Cartwright, L. (2018). Practices of looking: An introduction to visual culture (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Thibodeau, P. H., & Boroditsky, L. (2013). Natural language metaphors covertly influence reasoning. PLOS ONE, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052961

Thibodeau, P. H., & Boroditsky, L. (2015). Measuring effects of metaphor in a dynamic opinion landscape. PLOS ONE, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133939

Tutti, C. F. (2017). Art sex music. Faber & Faber.

Vale, V., & Juno, A. (Eds.) (1983). Industrial culture handbook. RE/Search Publications.

Van Gelderen, M. & Masurel, E. (Eds.). (2012). Entrepreneurship in Context. Routledge.

Webb, R. (2009). Ekphrasis, imagination and persuasion in ancient rhetorical theory and practice. Routledge.

White, J. C. (2015). Toward a theory of arts entrepreneurship. Journal of Arts Entrepreneurship Education, 1(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.46776/jaee.v1.33

White, J. C. (2019). A theory of arts entrepreneurship as organizational attack. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 8(2), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.34053/ artivate.8.2.3

Zabel, L. (2016). Meaning-making and arts entrepreneurship. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 5(2), 5-6.

Zagacki, K. S. & Gallagher, V. J. (2009). Rhetoric and materiality in the museum park at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 95(2), 171-191, 10.1080/00335630902842087

Comments